Last year, I coached the only American high school cricket team outside of New York City. It was created by a group of American kids who, without ever having played a hardball game, had already fallen in love with the sport. How did this come to pass? Well, it all started in Virginia, in April of 2008.

As a U.S. History teacher at the Cardinal Gibbons School in Baltimore, I often led field trips to the many historic sites in the area, and that April, I led a group of students on a two-day visit to Civil War sites in Richmond. Our first stop was the American Civil War Center at the site of the Tredegar Iron Works. After watching a cannon-firing demonstration, a smallish man in period clothing called out to our group, asking if we would like to play cricket. We agreed to have a look at the game, and from that point on, my life has had an added dimension.

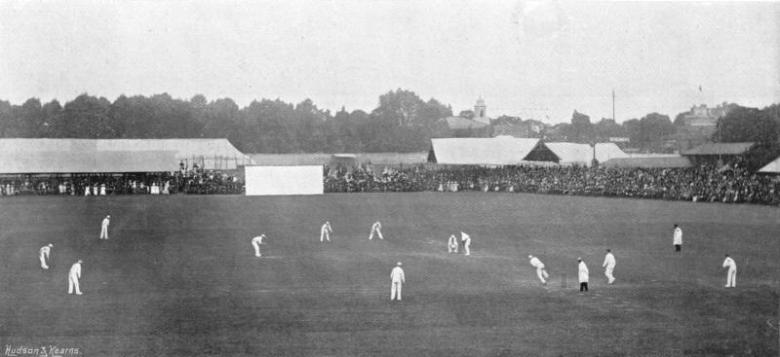

The man was Tom Melville, an interpreter who has spent many years introducing hundreds of Americans to cricket at festivals, fairs, and reenactments in over a dozen states and Canada. He’s also the author of “Cricket For Americans” and “The Tented Field: A History of Cricket in America.” He learned cricket at the University of Wales, but he now lives in Wisconsin. We gathered around Tom, and he gave us a very simplified explanation of cricket.

Listening to Tom Melville are (from left to right) Don Erdman, Don Grey, Will Arsenault, Will Berkey and Ryan Kelly

The same group, with Tim Schmidt and myself in the photo

In this modified version, a rubber ball was pitched underhanded, but otherwise, the basic rules applied. Our group was soon split into two teams, and before long, we were playing the centuries-old game of cricket.

Student Ryan Kelly calling his shot, a la Babe Ruth.

Current UMBC Student Will Arsenault, who was the “Man of the Match”

We probably played for about an hour, and it turned out to be the most fun we had all weekend. While we were still in Richmond, the boys were already talking about finding a way to play cricket after they returned to school in Baltimore. I said supportive things, but didn’t really believe that their new infatuation would last. I was wrong.

By the time I got back to my classroom on Monday morning, a nascent cricket club had already begun to develop. All that Monday, students kept showing up in front of my desk, asking when they would be able to play cricket. At that point, however, we had no equipment of any kind, not even a ball. So I went home that night and started spending my money online – soft cricket balls, Kashmir willow tennis ball bats and plastic stumps sets all went on my credit card. I trusted that I could eventually get my money back, but honestly, I wasn’t sure if the fad would last long enough for that to happen.

Once the cricket gear came in, I took the boys to an open part of the athletic field and set up the wickets. From that point on, the game took care of the rest. The students organized themselves into teams and taught themselves the game; I mainly watched, acted as occasional umpire and collected up the gear when they were done. Soon, after-school cricket had a fairly large following at Cardinal Gibbons.

Keith Hess places a stroke to the Forward Short Leg

Chris Sutton makes solid contact

Every day after school, there would be a dozen or so students in my classroom, nagging me to quit working and start cricket. My history classes also became diverted by students trying to move the subject to cricket, rather than schoolwork. On rainy days, we watched the Indian Premier League on my laptop, and discussed rules, players and nations. By the month of May, there were over 50 cricket players, and they wanted something more organized. We sold polos, collected money for more equipment and uniforms, and made plans to divide the boys into four teams for a fall league.

These teams then played a ten-week intramural cricket season, on a real cricket mat, starting in August when we reconvened at school. Members of the Baltimore Cricket Club, led by Gregory Alleyne, volunteered to help teach the boys the game, which was the first time that any of them had any real coaching. It went incredibly well, and the league was even featured in a story in the Baltimore Sun.

The photograph that appeared in the Sun.

Fast bowler Don Erdman

Will Foy

After we had crowned a champion that November, many of the players weren’t content to leave it at that – they wanted to play real cricket, with real, alum coated, rock-hard cricket balls. Fortunately, the family of an alumnus, the Patidars, had a pallet’s worth of real cricket equipment shipped to us from Mumbai, so, with just one more round of contributions, we had everything we needed, except, of course, other teams to play against.

With only a vague plan to play demonstration matches at area high schools in place, the Cardinal Gibbons Cricket Team began workouts inside the frigid gymnasium in January. There was a bit of conditioning, a bit of skills work and then a pick up game at the end of each Saturday’s practice. An eight-grader who was unsure about whether to come to Cardinal Gibbons or Archbishop Curley, Ashker Asharaff from Sri Lanka, started practicing with us, and was soon accepted as “one of the guys.” Gregory Alleyne stopped by occasionally to work with the boys, too. It was around this time that Megan Godfrey of the Baltimore Cricket Club put us in contact with Keith Gill, of the Washington Metropolitan Cricket Board, who at that moment was trying to organize a youth cricket league. A prayer had been answered.

Ashker Asharaff

Not long after, Keith visited us at practice, accompanied by Gladstone Dainty, President of the United States of America Cricket Association, which is the governing body of American cricket. Dainty watched us practice for a time, and then got involved personally, helping the guys with their technique. He really seemed to be enjoying himself. After practice, he spoke to the team, telling us how important it was for cricket to spread to kids like themselves, who had no cricketing background.

(From left to right) Justin Bruchey, Gregory Alleyne, Jamie Harrison, Keith Gill, John Boland

Mr. Dainty & me

Don Erdman bowls to Mr. Dainty

(From left to right) Will Berkey, Gladstone Dainty, Jon Marshall, Justin Bruchey

By March, temperatures had risen enough to allow us to practice outside, and we were soon joined by two new coaches, Trevor Roberts and Mike Thomas of the British Officer’s Cricket Club of Philadelphia. Every week, the team worked out on the football field. (Which they did not destroy. This, for some reason, was a great fear of the groundskeeper, who had somehow convinced himself that cricket was harder on grass than football. Go figure.) By May, the time had come to play our first match.

Finally, the pre-game ceremony ended, the moment of truth arrived. It was time to play cricket.

The first Gibbons batters, Justin Bruchey and Will Berkey

Justin Bruchey

Will Berkey

Jeff Thornton

Keith Hess

Don Erdman

Even though we were only playing 20 over matches, we lost bad in our early matches, usually by over 100 runs. But we accepted our fate, since we were playing against experienced cricketers from cricket-playing countries. In June, we became more international, being joined by Jayson Delsing, a player from South Africa, and Quincey Samuels, from Jamaica. Later two brothers of Indian descent from Philadelphia showed up at our match, asking to play. Having added our own experienced cricketers, the gap closed considerably.

Jayson Delsing and Quincy Samuels, our “ringers”

During the year or so that we had been playing cricket, I had been working long and feverishly to generate publicity for our program. My efforts paid off rather well, I think, as we received print coverage in the Baltimore Sun (multiple times), the Catholic Review and the Press Box. We also were discussed on 98 Rock‘s morning radio program. We also got quite a bit of coverage from the online cricket media, including Dreamcricket and Cricket World. For a time, it seemed like the world was watching us.

Another thing I did to garner support was to send emails to the major test-playing nation’s governing cricket bodies. Only Cricket Australia responded, and they were absolutely fantastic. I exchanged many emails with CA’s Rebecca Mulgrew, who put me in touch with Dave Tomlin of Western Australia’s Kent Street Senior High School’s cricket program and sent me a lot of great coaching materials. She told me how much Australia wanted to see cricket succeed in America, and while they knew it would be “tough slogging,” CA would be following us closely. Here’s a letter she sent me:

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that I quickly became Cricket Australia’s #1 American fan, and many of the boys started following Punter and the Aussies as well.

Another great experience I had was to be a part of the West Indies Cricket Board Level 1 Cricket Coaching Course, the first ever held in the United States. Windies coaches Wendell Coppin and Stephanie Power were great, and I was able to network with many of the Atlantic Region’s key people. I also spent a lot of time talking up the need to develop youth cricket in America, and how I believed that our program was just the beginning. Officials at USACA were really excited about what we were doing, and they looked forward to helping us grow.

In mid summer, it seemed like we were ready to take cricket to the next level.

For the first six months of 2009, we had been a magnet for cricket aficionados from all over the Mid Atlantic. At practices, guys from Pakistan, India, and other cricketing nations would show up to watch, talk cricket and ask about our plans. Many of these people were doctors and independent businessmen with teenagers at home who longed to play cricket. I received phone calls from investors who wanted to know if Cardinal Gibbons was interested in various “partnerships.” I began thinking about how our program might take advantage of being “the only game in town” for those in America who loved cricket.

At about the same time, I was told by David Brown, the school’s principal, that due to drastic budget cuts, I was being laid off from teaching. Enrollment was down again, I was told, and 40% of the tuitions of those who were enrolled were in arrears, which made the school a budgetary disaster. For too long we had been accepting any student that applied, regardless of ability to pay, and now the Archdiocese had given the school a year to get its act together. (The Archdiocese had just announced the closing of Towson Catholic High School, and there was a somber feeling at Cardinal Gibbons, wondering if we were to be next.) I went home that night, and after having made a few phone calls, knew what to do.

I spent the next few days designing a plan that would save cricket and Cardinal Gibbons School at the same time. It seemed like an idea, that, if not perfect, was at least guaranteed to reverse the school’s enrollment conundrum.

What I proposed was that Cardinal Gibbons School become the home to the United States’ first cricket academy. We would add elective courses in cricket (we already had elective courses such as “weight training” and “Gym II”), teach the game in Phys Ed classes and generally, make cricket an important part of the Gibbons culture. By doing this, we would attract the children of expatriates, such as the doctors at St. Agnes Hospital across the street. My experience with this group of students was that they were typically high achievers from well-off families – exactly what Gibbons needed to turn around its enrollment mess (I had two prospective students’ applications already in hand). I would become a cricket student-athlete recruiter, personally visiting clubs, associations and private homes, scouring the area for likely candidates. I also proposed a plan to spread cricket to gym classes at the middle and elementary schools, which even if only partially successful, would create a ready-made feeder system for Gibbons. We would also become a magnet for the investors that had been looking for a place to put their money. This plan worked for cricket and Cardinal Gibbons – the prototypical win-win. The only thing I needed was for the school to provide the start-up money to launch.

I first pitched the plan to the Archdiocese, which after a few days, called me back to say that they endorsed the plan, and that the Archbishop was “intrigued” by its potential. Next, I spoke to the Mr. Brown, explaining the importance of changing the trajectory of the school’s enrollment, in light of what was happening to Towson Catholic. He seemed supportive, but told me that he could make no budgetary decisions without first getting the approval of the school board. A few days later I met with Jonathan Smith, President of the school board, and explained the plan. Smith seemed less impressed. He told me that the school board had decided that there would be no new investment in the school for the coming year; their entire focus was on slashing expenditures as deeply as possible, and trying to raise money to offset the budget deficit, with the goal being a balanced annual budget. He was convinced that if this was done, the Archdiocese would not close the school.

When I explained that the Archdiocese, in public comments after the closing of Towson Catholic, had made it clear that enrollment trends were a critical factor in whether to close a school, Smith seem uninterested. The school board, I was told, was certain that the only consideration would be whether or not the school was in the black by December. Anything that jeopardized that would not be considered. Plus, the board had already decided to give a private individual $3500 a month to fundraise for them. It was suggested that I ask the alumni to invest in my plan.

That July, the Alumni Association had responded to the crisis with a plan of its own, the “Gibbons Forever Endeavor,” which was a complicated attempt to reorganize the school’s fundraising database, presumably with a fundraising push then to follow. At the first meeting to announce this initiative, I was allowed to pitch my plan, but none of those in attendance, save Carmel Kelly (an early supporter), saw any value in it. Alumni I spoke to individually said that they would continue their habit of donating only to sports teams that they favored. I found this attitude mind-boggling to say the least. It was like watching people rearrange deck chairs on the Titanic.

Scrambling, I called potential cricket investors, whose enthusiasm was dampened by the idea of sinking money into a school that either didn’t care for cricket that much, or was so near to closing that they couldn’t even provide the seed money for it. I was repeatedly told that their money was contingent upon the school’s firm commitment to the academy. Exasperated, I returned to the school board, which once again rejected the plan. The Archdiocese, along with a number of parents interested in sending their kids to Gibbons, asked me how things were going – I had no good news to report.

I began to wonder if the disinterest was a result of cricket being too “foreign,” or maybe because most of the players were honor students instead of “jocks.” I know that the other sports programs at Gibbons resented the attention that cricket had been getting in the press, and that the groundskeeper had long been agitated with me for forcing the football team to share its field with us. (He actually said to me, “That is a football field, not a cricket field!”) Once, his lawn tractor that was used to mow the grass had run over a lost cricket ball, and he demanded $38 in compensation for the “damaged blade,” even though it routinely ran over baseballs with no ill effects. I paid the $38.

By August, the cricket season was over and it was clear that my efforts to start a cricket academy had failed. I returned the few thousand dollars that had already been donated by cricketers, and called the investors to let them know. On a sad day in August, I returned to Cardinal Gibbons one last time to collect my personal belongings and return my key to the barn shed where the cricket equipment was stored, leaving the school to its fate.

And so, what may have been the last, best hope of the Cardinal Gibbons School was locked away inside a shed, never to be seen again. And that, perhaps, is the greatest tragedy of all.

“According to a study published in the journal Pediatrics in August that examined U.S. emergency room visits from 1997 to 2007, the number of concussions related to the five most popular competitive youth sports more than doubled among this age group, even though participation in those sports declined slightly. Among 14- to 19-year-olds, the number of concussions tripled. Altogether, there were about 250,000 concussions among young competitive athletes.

“According to a study published in the journal Pediatrics in August that examined U.S. emergency room visits from 1997 to 2007, the number of concussions related to the five most popular competitive youth sports more than doubled among this age group, even though participation in those sports declined slightly. Among 14- to 19-year-olds, the number of concussions tripled. Altogether, there were about 250,000 concussions among young competitive athletes.